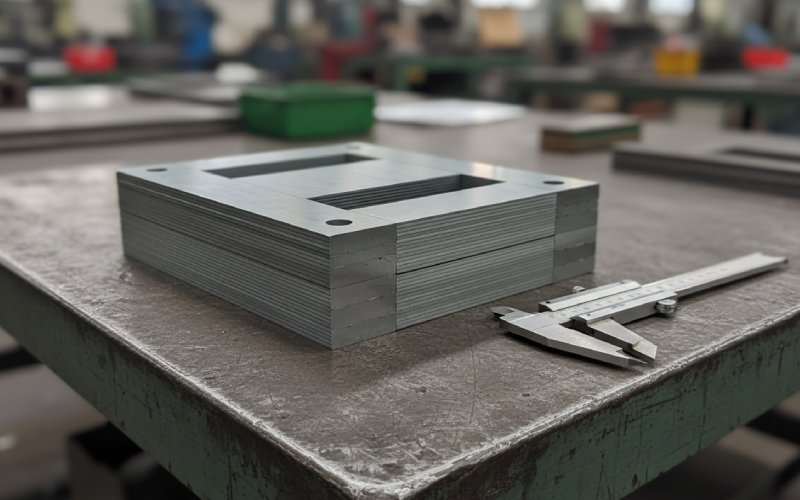

Sino의 라미네이션 스택으로 프로젝트에 힘을 실어주세요!

프로젝트 속도를 높이기 위해 라미네이션 스택에 다음과 같은 세부 정보를 레이블로 지정할 수 있습니다. 허용 오차, 재료, 표면 마감, 산화 단열재가 필요한지 여부, 수량등 다양한 기능을 제공합니다.

You order CRGO 라미네이션 with the same grade, same coating, same drawing. Yet no-load loss goes up 8%. Magnetizing current creeps beyond your design spreadsheet. Noise shifts.

“Same spec, different result.” This article is about that gap.

On paper, a batch of CRGO laminations is defined by:

What’s less visible is the scatter 내부 the mill’s tolerance window and how your own slitting, cutting, stacking, and annealing either amplify or damp that scatter. Grain-oriented steels are highly structure-sensitive; modest shifts in chemistry, texture, grain size, and internal stress give measurable changes in loss and permeability.

So two batches that both “meet spec” can produce noticeably different cores once you’ve punched, stacked, and clamped them. That’s the core of performance drift.

Let’s walk the chain, from slab to finished lamination stack.

Even within one grade, mills tune Si, Al, C, N and inhibitor species (MnS, AlN, etc.) to drive secondary recrystallization and Goss texture. Small shifts here affect grain size distribution and final magnetic properties.

You see it as:

Two coils from different heats, same nominal grade, won’t respond identically to the same line.

Goss texture sharpness and grain size distribution set the baseline loss and permeability. Research continues to show that small changes in recrystallization conditions, inhibitor dispersion, and annealing temperature can shift texture and grain growth behaviour, which then feeds straight into core loss.

You can’t fully “fix” that downstream, only avoid making it worse.

ASTM A976 C-classes (C-0…C-6) differ in chemistry, insulation resistance, friction, and intended stress-relief behaviour.

Two things happen:

If you change supplier or coating class “but keep everything else”, batch drift is almost guaranteed.

By the time the strip leaves the slitter, a lot of the later drift is already baked in.

High burr and heavy rollover are not just cosmetic. They:

This raises localized eddy current loss and hysteresis loss and often shows up as higher core loss and noisier cores. Industry experience and motor/transformer lamination studies consistently link higher burrs to higher loss and poorer efficiency.

Burr drifts with:

So a batch that happened to be slit late in the knife-life curve will quietly perform worse.

Strip camber, edge wave, and width variation are usually “within tolerance” until you start stacking and see:

All of which show up as higher magnetizing current and sometimes “mystery” no-load loss drift.

As designs move toward thinner gauges and more complex geometries, the cutting process itself becomes a noticeable variable. Mechanical shearing, notching, laser cutting, and advanced core cutting lines impose different stress states and heat-affected zones on the edges.

One batch cut on an older mechanical press line and another on a newer precision cut-to-length line can test differently even with identical coil and drawings.

Now the strip becomes parts. Every tool and press setting starts to matter.

As punches wear:

Press shut height, die clearance, lubrication, and speed move around as people tweak for throughput. Day-to-day variation here is one of the most common real-world reasons for lamination performance drift. It rarely makes the datasheet, but you’ll see it in microscope photos and in core loss.

CRGO depends on the rolling direction aligning with your main flux paths. Mis-orientation (even a subset of laminations rotated 90°) dramatically increases local loss and magnetizing current.

In production, this can happen when:

The batch looks fine visually. The test bench disagrees.

Sharp inside corners, over-tight pilot holes, and heavy forming all concentrate stress. GOES is quite sensitive; local stress shifts the B-H curve and magnetostriction. Even if your drawing is identical, subtle press adjustments change how hard you “work” the steel, and thus the loss.

You can ruin good laminations with sloppy stacking, or make mediocre material look acceptable with disciplined stacking. That alone tells you how strong this link is.

Standards and mill catalogues talk about lamination factor (stacking factor) for neat, idealized stacks. Real stacks, with burr and coating, rarely match that.

Drivers:

If your CAD model assumes 100% iron and the actual lamination factor slides from 96% to 93%, flux density moves, and so does loss and magnetizing current.

Local loss distribution in T-joints and overlaps depends strongly on overlap angle, length, and layer pattern. Studies show localized core loss increases from outer to inner edges in mixed-angle step-laps when alignment is off.

Real life sources of drift:

You end up with the same bill of materials, but a different local flux picture.

Under-clamped cores buzz and move. Over-clamped cores have extra mechanical stress and can show higher loss. Uneven clamping creates spatially varying performance: some legs run closer to spec, some worse.

Batch drift appears when:

Stress relief annealing is one of the strongest levers on CRGO performance, because it relaxes the cold-work from slitting, punching, and stacking. Many datasheets assume strips are stress-relief annealed when quoting best loss values.

Drift shows up when the real process deviates:

Result: one month the process truly relieves stress; another month it only halfway does.

Finished core tests will reflect that.

There’s also the subtle “do damage after annealing” issue:

All add fresh stress after you’ve paid for the furnace.

This part feels mundane. It is not.

Some markets see imports of “seconds and defectives” CRGO material, which come with looser control on flatness, burr, camber, and properties. Industry voices have highlighted how edge burr and camber in such material directly worsen stacking factor and core losses.

If your lamination plant occasionally backfills with this type of material when prime stock is tight, batch-to-batch drift is inevitable, even if the nameplate grade remains the same.

Poor storage – high humidity, condensation, rough stacking – can:

All translate into higher interlaminar loss and sometimes increased noise.

Re-stamping, re-grinding, or re-stacking laminations from rejected cores or prototype runs saves steel in the short term and injects inconsistency in the long term. Each extra handling step adds stress, possible scratches through coating, and geometry scatter.

A lot of what is labelled “performance drift” traces back to how you compare test data to mill data.

Mill guarantees are usually based on Epstein strips: stress-relief annealed, ideal grain orientation, simple magnetic path.

Your assembled core is:

Comparing those results one-to-one will always show a gap. What matters is how that gap changes over time.

If your process adds a roughly constant “penalty” to the Epstein result, drift is low. When your own process scatters, drift is high. Many companies don’t track this delta explicitly, which makes root-cause work slower.

Even good labs see shifts in:

No-load loss is sensitive to induction, frequency, and temperature, and temperature alone can noticeably change loss in GOES.

Before blaming laminations, it’s worth confirming that the test bench, its wiring, and its software haven’t changed.

Use this table as a starting filter when a batch of CRGO lamination stacks behaves differently from the previous one.

| Symptom in routine tests / FAT | Likely cause cluster | Fast things to check first | Medium-term fixes |

|---|---|---|---|

| No-load loss +5–10% vs last batch, magnetizing current also higher | Burr increase, poorer stress relief, lamination factor drop | Measure burr height on current vs previous batch; check furnace loading and soak data | Tighten burr limits in PO; define max tool strokes per sharpening; qualify furnace recipes per core size |

| No-load loss up, magnetizing current roughly unchanged | Localized loss in joints, coating/insulation issues | Thermography on core under test; look for hot joints; check coating class or supplier change | Standardize step-lap patterns and stacking fixtures; lock down insulation spec and incoming tests |

| Magnetizing current up, loss only slightly up | Lamination factor change, grain orientation errors, clamping pattern change | Weigh stacks vs theoretical; verify rolling direction marks; check clamping torque history | Specify lamination factor tests; add poka-yoke for grain direction at line; redesign frame for more repeatable pressure |

| Noise increase with only modest loss change | Stress distribution, clamping, partial annealing | Listen for local buzz, inspect frame contact points; review furnace record for that batch | Improve core support and damping; tune clamping; review post-anneal operations (welding, grinding) |

| Large variation between cores built from same batch of laminations | Assembly and stacking variation, test setup drift | Compare stack geometry, joint patterns, and torque logs; cross-check test bench with reference core | Standardize work instructions; automate or fixture more of the stacking; add regular test-bench calibration checks |

You can’t remove all variation in grain-oriented electrical steel. But you can design your lamination supply and core production so that most of the variation is upstream and transparent, not hidden inside your own plant.

Typical moves that help:

Done systematically, this turns “mystery drift” into a set of controlled variables.

You’ll never get zero spread. Many transformer OEMs treat ±3–5% variation in no-load loss between batches (at constant design and test conditions) as normal. Tighter than that usually requires very controlled slitting, punching, and annealing, plus good mill partnerships. When results wander beyond that band, it’s a sign to check tooling, furnace process, and incoming material records.

Yes. Burr is a proxy for edge strain and local geometry distortion, not just for turn-to-turn shorts. Even if insulation is intact, high burr increases localized flux density and introduces residual stress, both of which raise loss. Studies and industry experience link higher burr levels with higher core loss and poorer stacking factor.

Sometimes you can reduce the penalty, but you can’t change the underlying texture and chemistry. Stress relief mainly removes processing stress from cutting and stacking. If the higher loss is driven by mill-side differences (grain size, inhibitor distribution, texture sharpness), annealing won’t make the batch identical to a better coil; it just makes your own contribution more consistent.

It can be, but only if you also control your internal processes. Tighter mill specs reduce coil-to-coil scatter, which helps. If your own variation from burr, stacking, and annealing is larger than the mill’s scatter, you’ll hardly notice the improvement. The usual path is: stabilize internal process → then negotiate tighter mill tolerances that actually translate into lower spread at the core level.

Think in terms of data, not calendar. Track:

burr height vs strokes on each tool

core loss vs tool age and vs furnace load

variation between operators or shifts in stacking

Once you see where performance starts to degrade, set preventive maintenance or re-qualification limits just before that point. For many plants this ends up being tied to stroke count and measured burr growth curve instead of “every X months”, because production volume and material mix vary.