Laat Sino's lamineren Stacks Empower uw project!

Om je project te versnellen kun je lamineerstapels labelen met details zoals tolerantie, materiaal, oppervlakafwerking, of geoxideerde isolatie al dan niet vereist is, hoeveelheiden meer.

A lot of CRGO-laminering content quietly assumes a near-sinusoidal voltage and a clean magnetization loop. Reactors and many inductors don’t live there.

Grain-oriented steel behaves differently under these conditions than in the 50/60 Hz, sine-wave test used in standard loss ratings. A recent study on GOES wound cores at ~2 kHz even shows specific losses lower for square voltages than for quasi-sine at the same peak flux, because the harmonic content shifts where eddy currents concentrate in the strip.

So before picking “M3, 0.27 mm” out of habit, lock down:

Everything else—stacking factor, joint style, gap scheme—hangs off those four.

Datasheets will happily quote saturation around 1.9–2.0 T for grain-oriented electrical steel, with a reasonably linear region up to roughly 1.2 T.

In practice for power reactors and iron-core inductors you rarely want to be that brave.

These are indicative, not a substitute for your own B-H curves and lifetime model:

| Type toepassing | Typical design Bpeak in CRGO | Comment on margin |

|---|---|---|

| Shunt reactor (HV, oil-immersed) | 1.1 – 1.4 T | Strong focus on loss + hotspot control |

| Line reactor (LV/MV) | 1.0 – 1.3 T | Watch DC bias from converters |

| DC choke (AC/DC front-end) | 0.8 – 1.1 T (around DC operating point) | Flux offset dominates; gap is the main tool |

| Medium-frequency inductor (few kHz, CRGO) | 0.8 – 1.2 T | Tradeoff between size and core loss |

| Simple mains inductor / choke | 1.2 – 1.5 T | Often copper-limited rather than core-limited |

A classic cut-core design guide for grain-oriented steel shows useful “linear enough” behavior up to ~1.2 T even under DC bias if the gap is chosen correctly.

Voor line and shunt reactors, you usually run closer to transformer practice, but:

Voor inductors in switching supplies, you’ll normally accept lower Bpeak because:

Rule of thumb that keeps projects out of trouble: Design first against Bmax,hot,biased, not room-temperature Bmax. Then check whether the grade you wanted still makes sense.

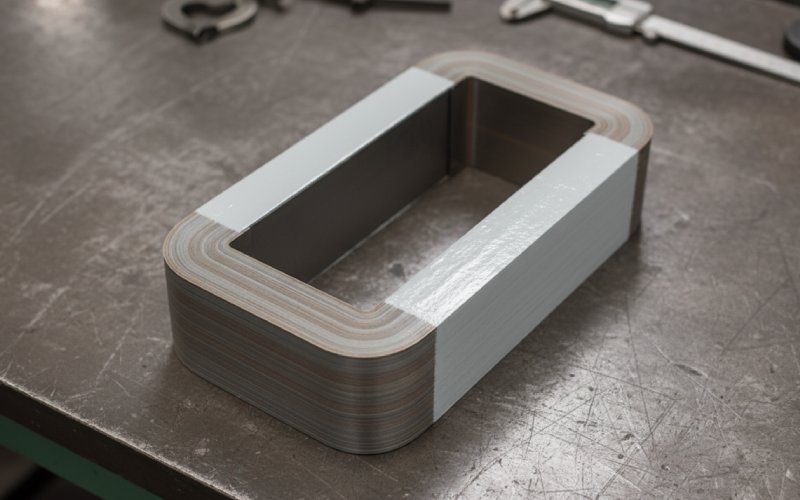

Everyone writes “stacking factor 0.96” on the slide. Reality is messy.

Stacking factor directly hits the effective iron cross-section. Lower factor → less steel → higher flux density than you thought → early saturation and extra loss. A standard magnetic-core handbook points out that misaligned burrs and poor insulation between laminations can easily erode stacking factor enough to matter at power levels where CRGO is used.

Belangrijkste punten:

Voor reactor cores, stacking factor is slightly more forgiving than in high-efficiency transformers, because many designs are already gap-dominated. But once you move into high-flux, low-loss HV shunt reactors, small errors in effective area show up as extra watts and unexpected hotspot locations.

You don’t need to put all of this in the RFQ, but design around:

If you are reusing a transformer lamination tool for a reactor, double-check that the Echt stack height after coating and pressing still matches the magnetic design. It often doesn’t.

CRGO lamination blogs spend a lot of time on step-lap for transformers. The physics carries over to reactors and inductors, just with different priorities.

In reactors:

Whatever joint you use, make sure your drawing and RFQ talk about:

Leaving the joint strategy “implicit” often ends with the supplier using their transformer default, which may not fit your reactor’s DC bias and waveform.

Gaps are where reactor cores quietly generate extra loss.

Academic work on iron-core shunt reactors with discretely distributed air-gaps compares:

It shows how distributing the gap can adjust inductance, leakage inductance, and loss separately, and how fringing around each gap adds local eddy-current loss.

For power reactors, this leads to a few design levers:

For inductors, a classic iron-core design guide for C-cores emphasizes:

So, don’t leave gap geometry vague.

And no, a “typical transformer gap practice” sentence in the spec is not enough when your reactor is expected to operate close to saturation under DC bias.

Most noise articles target transformers, but the same magnetostriction phenomena show up in largish reactors and inductors: laminations strain slightly as flux reverses, and the stack vibrates.

Recent engineering-oriented notes on CRGO magnetostriction make a few points that carry straight into reactor and inductor stacks:

For reactors:

Design checklist for the stack:

CRGO has reasonably high thermal conductivity and a high Curie temperature (often around 730 °C for standard grades).

Two consequences that matter in reactors/inductors:

For lamination stack design:

Thermally, CRGO will usually forgive you. The winding insulation system won’t.

Most RFQs specify grade, thickness, and coating, maybe “step-lap”. Standards guides point out that grade codes and loss tables only tell half the story; the rest sits in how the laminations are turned into a core.

For reactors and inductors, add some precision.

Specify:

Include:

For gapped CRGO cores:

You don’t need a million tests. But define a small, clear set:

This way, if a reactor later runs hot or saturates early, you can tie it back to either design assumptions or stack execution, without guessing.

Not exhaustive, but it catches many of the issues that show up late:

If any answer is “not sure”, that’s usually where future failure analyses come from.

Sometimes, but not blindly.

If the line reactor sees similar flux levels and no serious DC bias, a transformer-style core with step-lap joints and similar grade can work.

Once DC bias or large harmonic currents appear, you’ll need more gap and often a lower Bmax. That will change the optimum steel grade and stack height.

At minimum, re-run the design with realistic current waveforms and stacking factor, and review gap provisions.

Voor early estimates:

0.95 is a decent starting guess for modern thin CRGO with good coatings and trusted stamping.

Drop to 0.92–0.93 if tooling is old, thickness >0.30 mm, or burr control is poor.

But move to measured values (via mass or dimensions) as soon as you have first articles.

Grain-oriented steel tends to win when:

Flux density is high (0.8–1.2 T region)

Frequency is moderate (up to a few kHz)

Power is large, so ferrite volume would be excessive

Ferrites and powder cores win in the high-frequency domain, where core losses in CRGO are too large even at lower induction. The trade comes down to frequency vs Bmax vs volume vs loss.

Burrs affect:

Stacking factor (less effective iron)

Interlaminar eddy currents (more loss)

Design literature shows that mismanaged burrs can reduce stacking factor enough to push a supposedly “safe” design toward saturation.

If you are designing high-power reactors, it’s worth putting a numeric limit on burr height in the RFQ and asking for a simple measurement method (profilometer, sample checks per batch).

They can, but not automatically.

Studies on shunt reactors with discretely distributed gaps show that:

Distributing gaps can control inductance and leakage inductance more flexibly.

Fringing around each gap adds local eddy-current loss, so too many gaps can actually increase total core loss if implemented poorly.

So, distributed gaps are a design tool, not a free upgrade. They need to be supported by some analysis (analytical or FEA) and clearly dimensioned for the lamination supplier.

For CRGO reactors and inductors, avoid leaving these items vague:

Joint method and overlap

Gap dimensions and distribution

Target stacking factor range

Core loss test conditions (B, f, temperature, waveform)

Those four non-decisions are where most surprises come from when the prototype hits the test bay.