Let Sino's Lamination Stacks Empower Your Project!

To speed up your project, you can label Lamination Stacks with details such as tolerance, material, surface finish, whether or not oxidized insulation is required, quantity, and more.

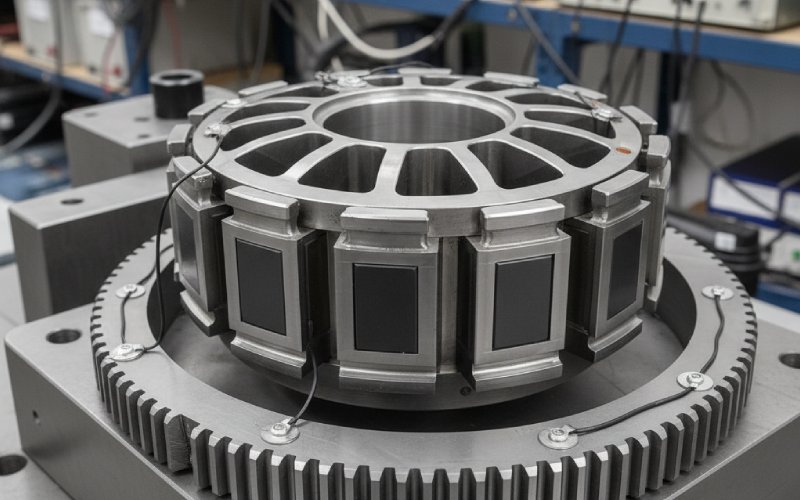

Most design stories in a permanent-magnet machine are written by three numbers: airgap, tooth width, and rotor rib thickness. Airgap sets the scale of torque and flux, tooth width decides how cleanly that torque arrives, and rib thickness decides whether the rotor survives while still giving you saliency. Once you see it that way, the rest of the optimization is just arguing about secondary consequences.

In the literature, you see dozens of knobs: magnet span, slot opening, bridge width, barrier shape, skew, tooth tip geometry, and so on. But when people actually run structured sensitivity studies, the same pattern keeps appearing. For average torque and power factor in IPMSM and synchronous reluctance variants, the effective airgap dominates the first-order influence, with rib thickness and other rotor dimensions acting as second-tier modifiers.

Robust design work on surface-mounted machines makes a related point from another angle. When you compute partial derivatives of objective functions such as overall core area flux (OCAF) with respect to design variables, the airgap length appears both in the mean response and in the variance, especially once you include manufacturing tolerances. Larger airgaps reduce both OCAF and its sensitivity, at the price of torque, so the “best” point is never a simple minimum or maximum; it is always a negotiated compromise.

Tooth width rarely wins a one-variable-at-a-time ranking, yet it has a habit of reshaping everything else you thought you understood. Analytical models for unequal tooth width and modular stators show that tooth width, together with flux gaps, changes not only slot permeance but also effective winding factor and flux focusing or defocusing. That means the same airgap and magnet volume can give you markedly different back-EMF and torque when you start distorting tooth geometry.

Rotor rib thickness is the stubborn one. Studies on IPMSM traction motors in flux-weakening operation make it clear that rib thickness ties together three things you would prefer to treat separately: maximum power at high speed, mechanical safety factor in the bridges, and the d–q inductance pair that sets your saliency. Try to change one and you inevitably move the others.

So the short version is simple and slightly uncomfortable. Airgap length is the loud variable for electromagnetic output. Tooth width is the quiet one that rearranges harmonics, losses, and slot utilization. Rib thickness is the one the mechanical engineer will make you justify in a design review.

If you read the torque ripple sensitivity work by Degano and Bianchi on synchronous reluctance and interior PM machines, you see something that feels almost unfair. When they sweep rotor outer diameter (and therefore airgap), and iron rib thickness, the map of average torque is dominated by airgap; rib thickness only modulates it.

For torque ripple the story is more nuanced. At small airgaps, the influence of rib thickness on ripple can be substantial. At larger airgaps, rib thickness barely moves the needle. The same parameter is powerful in one part of the design space and almost irrelevant in another. Which is exactly the kind of behavior that makes sensitivity numbers hard to interpret without context.

Dynamic airgap modeling and experimental work on synchronous machines back up the intuition everyone already has from lumped parameter models: airgap length sits in the denominator of flux density and permeance expressions, so any uncertainty there multiplies directly into torque, noise, and loss. In other words, if you are only allowed to control one dimension with real care on the shop floor, it should probably be the airgap.

From a practical design perspective, airgap sensitivity also has an annoying side effect. It tends to mask smaller but still important influences from tooth geometry and rib shaping. You can make a careful tooth-width modification, then see most of its benefit washed out in prototypes simply because the as-built airgap moved by fifty microns in the wrong direction.

Unequal tooth width, modular stators, tooth-coil windings — all slightly unfashionable phrases compared with “new rotor topology,” but they show up again and again in papers that manage to extract extra torque or lower cogging without exotic materials.

Analytical work on unequal tooth width surface-mounted machines makes a few points that are easy to forget in a day-to-day optimization loop. First, tooth width is not just about slot fill and saturation; it influences the effective airgap permeance function, which means it quietly changes the harmonic content of the airgap flux density. That feeds straight into cogging, acoustic noise, and iron loss.

Second, the same tooth width pattern interacts strongly with slot/pole combinations. A modification that is beneficial for a 12-slot/10-pole machine can be neutral or even harmful for 12-slot/14-pole if the flux gaps and tooth tips shift the winding factor in the wrong direction. General rules exist in the literature, but they are often tied tightly to specific slot/pole sets and winding types.

In more recent work on improving single-layer tooth-coil windings, tooth width again appears as a primary lever. By redistributing tooth material, designers can improve winding utilization and adjust leakage paths without touching the rotor at all, which is attractive when the rotor comes from a supplier or is shared across platforms.

If you look at it from a sensitivity point of view, tooth width usually carries moderate first-order influence on torque and efficiency, but disproportionate influence on cogging, local saturation, and noise. That is why tooth width changes often feel “invisible” in basic performance plots yet show up clearly in FFTs of radial forces or in temperature maps.

For an interior PM machine, rotor ribs look like a small geometric detail. In practice they are where mechanical, thermal, and magnetic design all try to talk at once. Studies that relate rib thickness to maximum power in the flux-weakening region show the trade-off starkly. Thicker ribs improve mechanical integrity and reduce stress under high-speed operation, but they push the machine toward lower saliency by choking the flux barrier, which directly affects field-weakening capability and power factor.

Rotor design theses and experimental IPMSM work report similar observations: once ribs become too thin, you start to see unacceptable stresses and manufacturing sensitivity; once they become too thick, d–q inductances collapse toward each other and the machine behaves more like a surface-mounted design, with the expected penalties.

In the torque ripple sensitivity maps mentioned earlier, rib thickness plays a secondary role for average torque but a strong role for ripple at specific airgap values. That is an awkward combination. It means that if you weight torque ripple strongly in your objective function, rib thickness may look “important,” even though its influence on other key responses is limited or even negative.

So for sensitivity analysis, rib thickness rarely shows up as the global winner, yet it is difficult to treat as just another minor dimension. The cost of being wrong is not a small efficiency loss; it can be cracked bridges or a machine that cannot hit its field-weakening targets on a real drive cycle.

Suppose you build a parametric model of a 12-slot, 10-pole IPMSM intended for traction use. You pick three continuous design variables: airgap length (g), stator tooth width (wt), and rotor rib thickness (w{rib}). You choose a reasonably tight operating envelope, a few torque and speed points, and compute Sobol-style first-order indices from a design of experiments, using FEA as the evaluator.

The specific values below are illustrative, but they are shaped to be consistent with trends reported in torque ripple and robust design studies for similar machines.

| Response (nominal operating point) | Normalized sensitivity to airgap (g) | Normalized sensitivity to tooth width (w_t) | Normalized sensitivity to rib thickness (w_{rib}) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average torque | 0.62 | 0.18 | 0.20 |

| Torque ripple (percent) | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.45 |

| Efficiency at base speed | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.25 |

| Peak von Mises stress in rotor bridge | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.95 |

| Power factor in flux-weakening region | 0.30 | 0.10 | 0.60 |

You could argue with every number in that table, but the pattern is hard to escape. Airgap is the main driver for average torque and still significant for efficiency. Rib thickness dominates mechanical stress and shares influence with airgap on power factor. Tooth width never tops a column, but it quietly shapes both efficiency and torque ripple.

Notice also that no response is controlled by a single variable. Even bridge stress, which is almost entirely a function of rib thickness in a freeze-frame mechanical analysis, will pick up cross-terms once you let the airgap and tooth width move enough to change rotor geometry or operating current. That is one reason simple one-at-a-time variation can give you a misleading sense of security.

Sensitivity analysis on clean CAD models is neat. It has sharp results and tidy indices. Real motors live in the mess of statistical spreads. Robust optimal design studies for PM machines make that painfully clear. When you carry tolerances on airgap, magnet thickness, and other dimensions into the model, you often find that a variable with modest nominal sensitivity produces large variation simply because its manufacturing spread is bigger.

For the trio we are talking about, you usually see something like this in practice. Airgap has high sensitivity and relatively tight control, but any eccentricity or bearing stack-up can blow your assumptions. Tooth width has moderate sensitivity but can suffer from tool wear and lamination tolerances, which interact with slot fill and insulation systems. Rib thickness tends to be specified tightly for mechanical reasons, yet casting, punching, or machining variances can still nibble away at your safety margin.

One subtlety from robust design work is worth keeping in mind. A design that increases the mean of a performance metric but also increases its sensitivity to tolerances may not be the right answer. Some studies explicitly optimize both the mean and the standard deviation of responses such as torque or OCAF, using hybrid response surface models and Taguchi-style ideas. With that mindset, you might willingly accept a slightly larger airgap or a more conservative rib thickness if it makes the machine easier to build consistently.

If you sit down with a blank design and only promise yourself to respect these three variables, a reasonably robust routine appears. You start by choosing a narrow corridor for the airgap. The corridor is set by mechanical clearances, expected eccentricity, thermal growth, and what your supplier can actually hold. Within that corridor, you still treat airgap as a high-leverage continuous knob, but you resist the temptation to push it to extremes.

Once the airgap corridor is fixed, you work the tooth width. Not just as a scalar, but as a pattern if unequal teeth or modular concepts make sense for your slot/pole combination. You watch how back-EMF and torque respond, of course, but you pay closer attention to cogging torque, radial force spectra, and core loss. That is where tooth width earns its keep. If your noise targets are aggressive, this is also the stage where you accept that some “nice-looking” flux plots will have to be sacrificed to avoid awkward force harmonics.

Rib thickness comes later than most people think. You start from a mechanically credible guess, perhaps informed by earlier designs or by a quick rotor stress analysis at overspeed. Then you adjust rib thickness jointly with operating current strategy and magnet layout, watching simultaneously three plots: d–q inductance difference, rotor stress, and high-speed power capability. Moves that look good in only one of those plots are suspect.

The uncomfortable but honest part is that this routine is not strictly linear. When you change rib thickness enough to reshape flux barriers, you effectively change the “equivalent” airgap as seen by some harmonics. When you change tooth width aggressively, you alter slot leakage and local saturation, pushing the optimal airgap corridor slightly. So you loop. Maybe twice, maybe more. That is normal.

Once you have run your own DOE or optimization and generated sensitivity plots, it helps to read them with a few questions in mind. If airgap does not appear as a major contributor to torque or efficiency in your analysis, is that because the range you allowed for airgap is too narrow, or because other variables have been given unrealistically wide ranges? If tooth width looks irrelevant, are you looking at the right metrics, or only at average quantities that wash out harmonic and loss effects? If rib thickness seems to dominate many responses, is that physical, or a sign that your design space puts you very close to mechanical limits?

Comparing against published work can keep you honest. If your machine is in roughly the same size and speed class as those in the torque ripple and robust design papers, your trend directions should at least rhyme with theirs, even if the magnitudes differ. If they do not, the problem might not be in the machine, but in how the sensitivity indices were computed or normalized.

The main lesson from both the literature and real development work is not that one of these three variables is magically more important than the others. It is that each of them owns a different part of the behavior space. Airgap sets the broad level of torque and flux and carries much of the manufacturing risk. Tooth width shapes waveform quality, loss distribution, and slot utilization, often without dramatic changes in headline numbers. Rotor rib thickness ties together mechanical safety, saliency, and high-speed power in ways that resist simple trade-off curves.

Design flows that treat these three on equal terms, and that include their tolerances from the start, tend to produce machines that work predictably in production rather than only on a clean FEA mesh. That is usually what matters when the prototype phase is over.