Let Sino's Lamination Stacks Empower Your Project!

To speed up your project, you can label Lamination Stacks with details such as tolerance, material, surface finish, whether or not oxidized insulation is required, quantity, and more.

The stator and rotor together usually dominate both material and processing cost, so if you build your bill of materials (BOM) around them instead of treating them as a black box, you get far more control over margin, risk, and design trade-offs.

Most public articles either stay generic (“laminations and copper are important”) or get lost in academic cost modeling. This guide aims to sit in the middle: practical enough to drive an Excel model today, and deep enough that your costed BOM is defensible in design reviews and sourcing negotiations.

Before touching a BOM template, zoom out: what kind of machine are you costing? A permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM) for an EV, an inner-rotor BLDC servo, or a bog-standard induction motor all have very different cost structures — especially in their stator and rotor.

Two decisions dominate everything that follows:

These choices define whether your cost is magnet-heavy, copper-heavy, or steel-heavy — and what level of tolerances, balancing, and testing are appropriate. For example, an outer-rotor BLDC hub motor may spend more on magnets and lamination diameter, while a high-speed inner-rotor PM machine spends aggressively on precise laminations, sleeves, and balancing.

Once that context is clear, your costed BOM is no longer an abstract spreadsheet; it’s a structured narrative of how this specific machine turns money into torque.

If you look at teardown-based cost studies and OEM “motor CBOMs” (costed BOMs), you’ll see that stator costing is never just “stator – $X”. It’s a set of tightly related but separable cost buckets: laminations, insulation, copper, impregnation, machining, and tests.

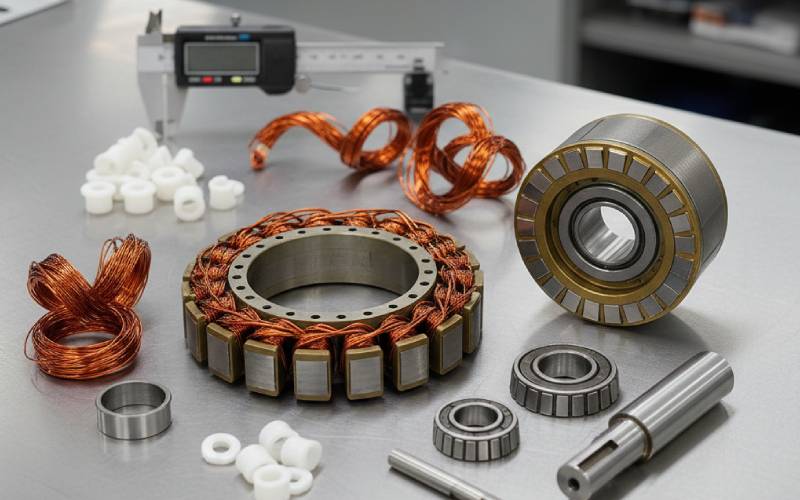

At a physical level, almost all modern stators are some variant of:

A good costed BOM makes these physical realities explicit. Instead of one vague “stator” line, you model: raw steel mass and scrap factor, press-tool amortization, winding method, impregnation process, and the test regime required by your customer spec.

Done properly, you can now ask informed questions like: “What if we move from segmented cores to a simple laminated stack?” or “What is the cost per percentage point of slot fill improvement?” and see answers in the CBOM rather than in hand-waving.

If the stator often dominates copper cost, the rotor frequently dominates risk: magnets that move with commodity markets, high-speed mechanical integrity, and manufacturing yield.

For induction machines, you might have a relatively “simple” squirrel-cage rotor — laminations plus cast or bar-and-ring conductors — but the die casting or bar brazing process and the required straightness and balance still carry meaningful cost.

For PMSMs and BLDC machines, the rotor stack is where your BOM feels every rare-earth price spike. Magnet volume, grade, coating, retention method (sleeves, cans, potting), and overspeed/burst requirements all translate to concrete cost lines that should stand on their own instead of lurking in a single “rotor – $Y” entry.

On top of that, you have the shaft, keys, couplings, and any integrated position sensing elements — all small individually, but material when multiplied by annual volume.

With stator and rotor broken into meaningful chunks, the next step is to express them in a consistent CBOM structure that links quantities (kg, seconds, machine-hours) to money. Most industry cost models for motors follow a similar pattern: each line item has material, process, and overhead components, with tooling and one-time engineering treated separately and amortized over an assumed volume.

Here’s a simplified table you can adapt directly into your BOM sheet. Numbers here are placeholders — the structure is what matters:

| Sub-assembly | Item category | Example line item | Primary cost drivers | Notes for stator/rotor CBOM use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stator | Raw material | Electrical steel laminations | kg × price/kg × scrap factor | Scrap factor depends on punching pattern and nest efficiency. |

| Stator | Conversion (labor) | Lamination stamping and stacking | Press time, operator time, OEE | Tie to press tonnage and strokes/min. |

| Stator | Direct material | Copper windings | Slot fill, conductor choice, copper price curve | Model scenario with Al instead of Cu. |

| Stator | Process | Winding and termination | Cycle time, automation level | Distinguish manual vs robotic lines. |

| Stator | Process | VPI / impregnation | Resin mass, tank time, oven time | Batch size has huge effect on cost. |

| Rotor | Raw material | Magnets (NdFeB) | Volume × grade price | Treat magnet cost as separate sensitivity input. |

| Rotor | Conversion | Magnet insertion and curing | Handling, fixtures, cure time | Include scrap/yield loss for chipping or demag. |

| Rotor | Process | Dynamic balancing | Balancing machine hours | Often surprisingly large at low volume. |

| Rotor | Raw material | Shaft and retaining rings | Material grade, machining allowance | Watch tolerance creep → rework cost. |

| Shared | NRE/tooling | Stamping dies, winding tooling, jigs | Tool cost ÷ lifetime volume | Keep these explicit, not buried in “overhead”. |

Once this structure exists, “what-if” design conversations become spreadsheet edits instead of arguments: thinner laminations, different magnet topology, segmented stator teeth — they all show up as parameter tweaks and you can see the impact on cost per kW or cost per Nm.

To pull this all together into something actionable, it helps to follow a repeatable workflow rather than re-inventing your CBOM every project. Think of it like a checklist you walk through with design, manufacturing, and purchasing in the same (real or virtual) room.

If you follow this pattern, your “costed BOM around the stator and rotor” stops being an after-the-fact accounting artifact and becomes a design tool: one that lets you reason clearly about where each dollar goes, why it’s there, and how to move it without breaking the motor.

And that’s the real competitive edge — not just knowing your stator and rotor cost, but being able to shape that cost with engineering intent.