Let Sino's Lamination Stacks Empower Your Project!

To speed up your project, you can label Lamination Stacks with details such as tolerance, material, surface finish, whether or not oxidized insulation is required, quantity, and more.

If you only remember one thing, let it be this: treat stack height tolerance and magnet–airgap alignment as a coupled random system, not two separate knobs. Once you simulate them together, the argument about whether you “really need” that extra 0.02 mm of tolerance tends to resolve itself.

Most papers isolate airgap length or magnet tolerances and keep everything else nailed to nominal. That is useful for theory, less useful for arguing with manufacturing.

We already know that even a 0.1 mm shift in airgap can move average torque by about one percent and torque ripple by more than fifty percent in some machines. At the same time, axial stack height shifts change end effects, axial leakage, stiffness, and how strongly the structure pushes the rotor into eccentric positions. You never see these two living alone on a drawing; they share parts, fixtures, and suppliers.

So if your variation model keeps stack height and airgap eccentricity independent, it quietly assumes exactly the thing you know is not true: that the 3D structure does not talk back to the magnetic circuit.

Several strands of work are already on your desk.

One set of studies treats airgap as the dominant geometric parameter. They show that small changes in gap length drive clear shifts in torque, torque ripple, inductances and flux weakening capability, and they warn about the usual trade-off between tight gaps and mechanical risk. Another stream looks at manufacturing tolerances statistically for axial flux machines and runs ten thousand variants; combined magnet and positioning tolerances send cogging and ripple torque several times higher than the nominal design suggests.

On the purely geometric side, tolerance stack-up work for permanent-magnet generators shows how a simple worst-case stack can squeeze an 0.8–1.2 mm airgap requirement into roughly 0.81–1.18 mm actual, and how reassigning tolerances to a few key features reduces the burden without redesigning the electromagnetic side. Measurements on real machines then confirm what the CAD promised and feared at the same time: airgap length, magnet remanence, and airgap flux density correlate in the expected way, but nominal values are often optimistic by several percent.

Finally, robust design studies on flux-switching machines already argue, with data, that slightly longer airgaps can cut unbalanced radial forces significantly while only trimming torque by around ten percent, and that manufacturing tolerances should be treated as normally distributed variables feeding directly into performance distributions. Space-grade magnetic gears that run with 0.25 mm gaps and tolerance bands down near ±0.03–0.11 mm then complete the story: tight airgaps are possible, but only when stack-up, structural deformation, and thermal expansion are solved in one combined model.

Useful work. But most of it either fixes the axial stack or pushes it into a single safety factor.

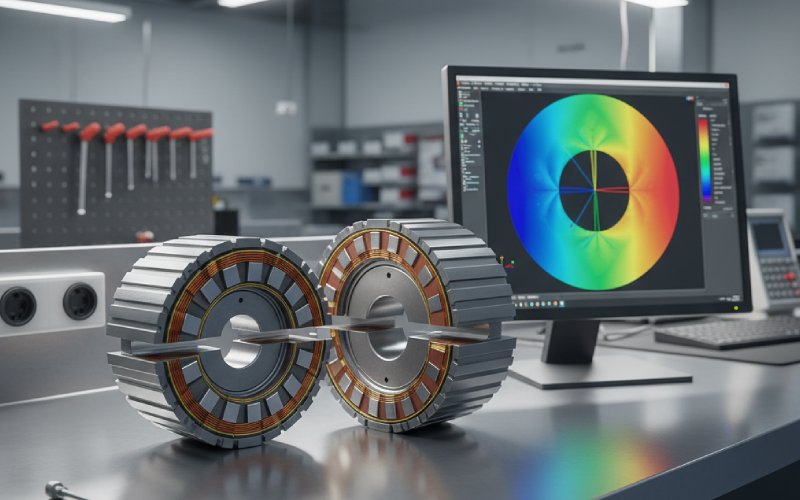

For the simulation to match reality, you need to choose what you mean by “stack height” and “airgap alignment” in a way that maps to machining and assembly.

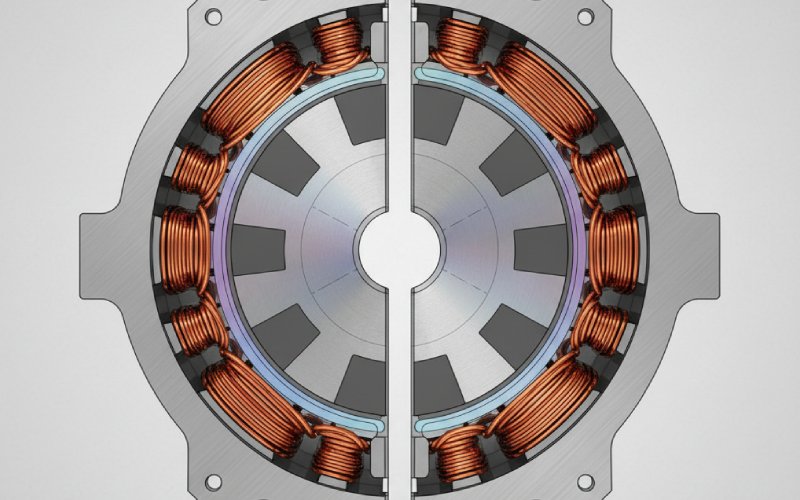

Stack height is not just the lamination length. It is the net axial build of every element that pushes flux into the gap: laminations, end faces, magnet carriers, shims, even adhesive layers if they are thick enough to matter. On the rotor side, stack height variations can change where the magnets actually sit relative to the stator teeth in the axial direction. On the stator side, they decide how well the active steel overlaps the magnet stack.

Airgap alignment has at least three pieces. There is the mean radial gap. There is the eccentricity, which is how off-center the rotor is. Then there is the skew between stator and rotor along the axial direction, which appears whenever the two stacks are not equal or not square. In short machines, that last one starts to hurt much faster than 2D drawings suggest.

The coupling lives in the constraints. One machining fixture may set both lamination stack height and bearing shoulder position. Shim choices that fix thrust endplay change where magnets sit in the stator window. If you do not encode those links, the Monte Carlo clouds you plot will be cleaner than the ones nature gives you.

At this point you already have drawings and ISO or ASME tolerance classes. That is enough to build the random variables.

You start from part-level dimensional and geometric tolerances, then map them into a small set of effective variables: rotor stack height, stator stack height, mean airgap, eccentricity, and any key tilt or skew angles. Classic stack-up methods give you the algebra, whether you use worst case or something closer to root-sum-square. Relationship constraints come straight out of the datum scheme; one datum shift may move several surfaces together.

Then you assign distributions. For high-volume machines, normal or truncated normal often matches measurement data; for some low-volume parts, you might stay closer to rectangular or “spec-bounded but biased” distributions. The important thing is not the exact shape; it is keeping correlated quantities correlated. If one grinding operation simultaneously defines both airgap and rotor stack height, their deviations are not independent no matter what the tolerance table says.

For the magnetic model, the usual pattern still holds, but you use it differently.

You keep your 2D model for fast sweeps of mean airgap and eccentricity in the mid-plane, calibrated against a handful of 3D runs that include actual stack heights and end effects. The 3D runs give you correction factors as functions of rotor and stator stack mismatch and any axial offset. Once those correction factors exist, the variation study can stay mostly in 2D or in a reduced-order magnetic equivalent circuit.

The trick is to define a small set of outputs that connect directly to tolerancing decisions. Average torque, torque ripple, back-EMF, local peak flux density in critical teeth, and some measure of unbalanced radial force are usually enough. Noise and vibration often follow from those.

You do not need to resolve every minor waveform detail for ten thousand virtual machines. You just need enough accuracy that performance shifts across your tolerance cloud are real, not numerical noise.

On the mechanical side, axial stack height determines stiffness and how loads distribute into the bearings and housing. Small changes in stack height can change which surfaces make contact, or how shims compress, and that in turn changes eccentricity under load.

A minimal but useful model combines:

A static structural representation of the rotor–stator–bearing system, including contact or preload where it matters, so you can compute eccentricity and tilt for each tolerance realization and each operating load case.

A thermal model that gives you temperature fields for the same operating points, since thermal growth can easily move your mean airgap by a few percent over life, as seen in space-application actuators.

Again, you do not need a full CFD or detailed contact model for every Monte Carlo sample. Precompute response surfaces: how eccentricity and tilt depend on the effective stack heights and a few loading variables. Then feed those into the magnetic model.

The table below is illustrative rather than pulled from a specific machine, but it shows the sort of interaction engineers actually argue about. Assume a nominal machine with 0.8 mm radial airgap, 80 mm stator and rotor stack heights, and some moderate torque ripple.

| Case | Rotor stack ΔL (mm) | Stator stack ΔL (mm) | Mean airgap g (mm) | Eccentricity e (mm) | ΔTorque (%) | ΔTorque ripple (%) | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | Design point used for FEA and testing |

| A | +0.20 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.02 | −0.5 | +15 | Longer rotor stack, slightly larger radial load, small eccentricity under torque |

| B | +0.20 | −0.10 | 0.76 | 0.04 | +1.0 | +40 | Stack mismatch pulls magnets closer on one side; reduced gap there, higher local B, strong ripple increase |

| C | −0.20 | 0.00 | 0.84 | 0.01 | −3.0 | −10 | Shorter rotor stack, slightly larger gap and lower stiffness, modest torque loss but better ripple |

| D | +0.10 | +0.10 | 0.82 | 0.00 | −2.0 | −5 | Both stacks long; mean gap grows due to assembly shims, ripple improves slightly |

| E | +0.20 | −0.10 | 0.72 | 0.05 | +1.5 | +80 | Same geometry as B, but under higher load; eccentricity grows, back-EMF and noise risk |

Once you run a few hundred real variants for your design, the pattern usually looks similar. Cases like B and E, where stack mismatch and airgap alignment conspire, define your yield limit. That is where machines still meet electrical spec on paper but fail NVH or mechanical clearance checks.

You can also see the outline of a solution. If you accept a slightly larger nominal airgap and rebalance the stack tolerances so rotor and stator lengths move together, you push the worst combinations away from the operating region. That matches the trend reported for FSPM machines where larger airgaps reduced unbalanced forces at modest torque cost.

The raw idea is simple: turn every key tolerance into a variable, sample them, and run the coupled electromagnetic and structural models. The difficulty is getting enough insight without burning weeks of compute.

A common pattern that works in practice looks like this, though every team dresses it differently. You do a designed experiment on the effective variables: rotor stack, stator stack, mean airgap, eccentricity, and maybe one or two others such as magnet remanence. A few dozen carefully selected points are often enough. For each point, you run the coupled model, capture the outputs, and fit a surrogate, either polynomial, Gaussian process, or something similarly light.

Once the surrogate passes basic validation, you use it inside the Monte Carlo. Millions of samples are cheap at that point. You can extract performance distributions, conditional plots such as “torque ripple vs rotor stack given good mean gap,” and, most usefully, the sensitivity of performance to specific tolerance contributors, not just to abstract dimensions.

The robust-design studies already show that when you treat tolerances this way, you can reduce the probability of failure significantly while accepting a small reduction in best-case performance. Your own surrogate model will tell you exactly what “significantly” and “small” mean for your design.

Variation simulation is only worth the effort if it flows back into the prints and process sheets.

First, you rank contributors. Not just “airgap matters most”, which is already known, but “eccentricity driven by rotor stack and bearing seat position is more harmful than mean gap variation driven by stator stack”. That gives you a rational basis for tightening one dimension while relaxing another, as the generator stack-up study demonstrated with its reallocation of tight tolerances from minor parts to the rotor shaft.

Second, you adjust nominal values. If the distribution of mean gap is skewed low because assembly tends to pull things together, as seen in measurements where average airgap ended up around five percent smaller than nominal, you can move the nominal up rather than chasing perfect centering. The variation model tells you how much margin you gain next to your no-touch mechanical limit.

Third, you check process ideas. Matching grinding steps, alternate datum schemes, or segmented stator assemblies all have obvious geometric consequences. You can turn each into a modified correlation structure in the variation model and see which one genuinely shrinks the performance spread. This is exactly what was done in the space-actuator work when match-ground bearing seats cut the predicted airgap tolerance band from around ±0.09 mm down to about ±0.027 mm.

There are some habits that keep this whole exercise grounded instead of drifting into pure simulation craft.

Always cross-check at least one dimension with measurement data, even early prototypes. A quick scan of actual airgap lengths and stack heights will tell you whether your assumed distributions are even close.

Keep the output metrics tightly tied to requirements: torque, efficiency, NVH proxies, clearance margins. If an output cannot change a drawing, it probably does not belong in the variation model.

Treat the electromagnetic and structural models as equal partners. If one stays nominal while the other varies, you will get confident-looking answers that are quietly biased.

Finally, resist the urge to over-polish the logic. Manufacturing rarely behaves as cleanly as a paper. Your variation simulation does not need to be theoretically pure; it needs to be close enough to factory reality that when it tells you stack height and airgap alignment should be treated as one coupled design variable, everyone in the room can see their own experience reflected in the plots.